A Love Affair With the Desert

By | Angus Taylor

Issue III, August 2018

...Which is the one thing that didn’t end up happening.

What happened instead was the last thing I had expected; a love affair with the desert.

The story begins with rope.

I was dreaming of the valley stone, the scent of pine, and watching last light high up on shimmering granite faces, but I had one road bump in an otherwise infallible plan... I needed more rope.

Luckily, this was something I had planned for. My solution to avoid carting three ropes from the ‘land down under’ to the US was simple and certainly cheaper: Buy the three ropes I needed in the US, and have them posted to a friend. Trouble was, the only person I knew living in the states at the time‒my good friend Bibi‒was currently living in Moab, which isn’t exactly a stone's throw from The Valley. However, it did happen to be the nearest major town to Indian Creek.

With this in mind, the plan was to do a brief stint in the desert, pick the ropes up, then double back to the real business: the big stone. I was an iron filling to the High Sierra’s great magnet, El Capitan.

Nine-and-a-half hours into the drive from San Francisco with two hours sleep in the last 30 hours, I entered a dream-like state. Rather than stop, I decided to pull in for a bag of red snakes. “That will keep me going,” I thought. “Only another five or so hours left.”

The bag's contents disappeared in under an hour and soon I was wide-eyed again, with nothing stopping me. At least for the next few miles.

It just so happened there was a roadblock.

Not a metaphorical one. The literal kind.

Trucks lined the sides of the highway for miles; they weren’t letting anyone through due to a chemical spill on the highway. Defeated, I pulled into a parking lot nearby to attempt to get some sleep, but this was no use at all. That entire bag of snakes felt like the equivalent of doing two lines of coke. There was only one thing left to do.

Peaking on sugar, I coasted my van towards the police blockade and wound down the window.

“G’day officer.”

“You’re Australian?” He said.

“Is there any other way around to get back on the highway?” I asked.

“Unfortunately, this is it, pal. You’ll have to pull up for the night.”

A brief moment of desperation overwhelmed me. I cleared my throat, in disbelief of what I wanted to say, but it just came blurting out anyway.

“Officer, I have a funeral to get to by tomorrow in Moab, and I’ve flown over especially to get to it…”

The guilt immediately washed over me. I felt like a naughty kid, lying to get out of school.

“A family member is it?” He asked.

“...Yes, my Aunt actually..” I almost choked on my words, what the hell was I doing (I’m so sorry Aunty Liss, please don’t disown me).

“One-second young man.” The police officer walked away and I could see him chatting on his radio.

He came back a few long moments later and said, “Son, this is quite the special circumstance. I’m going to let you through, you can rejoin the highway with a three-hour detour. You have to tell the next five blockades that it was on my order to let you through ok?”

After staring for a long moment, the guilt surely painted all over my face, I said, “....Ok. Thank you, officer!”

With a nod, he waved to another officer to raise the boom, “Oh and watch out for deer!” He said.

To the astonishment and visible outrage of a dozen truck drivers nearby, they opened the blockade and let me and my dodge just drive on through. I had the entire highway to myself.

I couldn’t believe it. Neither could the next five blockades of course, and it took a decent amount of sweet talking to convince them.

I’d done it. Guilty as charged. By the following morning, I would be climbing.

The Utah desert seemed like a place I couldn’t quite imagine with any sense of reality. Growing up as a kid in Australia watching classic westerns made the landscape seem like a make-believe backdrop that people stood in front of. Our oversized island drifting in the middle of the Pacific, made the American Southwest feel so far removed it became fantasy.

As my 15-hour drive was coming to a close, the truth slowly revealed itself to me.

The sun started yolking its way into the sky just as I was nearing Moab. At first, everything was ink black, light still only managing to form a thin lip on the horizon.

As the sun floated higher, the veil began to lift and when light finally spilled into the world my jaw hung open.

What remained was an unending colosseum of glowing orange rock. Ridges crowned with sand castle spires that looked frozen in time and jigsaw canyon walls cut out and into the horizon as if made by a giant cookie cutter. I was over-awed.

In comparison, the movies and photos were like Plato’s famous cave allegory; shadows on the back wall of a cave. I stopped the van, got out, and watched the sun chase the rest of the shadows away.

The first day ended up being an unbroken continuation of the last. Not long after I arrived I met up with my friend Bibi who had the ropes I’d bought. Without much delay, we were driving out to climb at Wall Street, a place that all residents of Moab know as the local outdoor climbing gym. I had barely come to terms with the fact people were belaying from the seats of their cars before I was tying in and pulling onto ‘Static Cling’ (5.11), my first taste of American stone. As flash pump and weariness set in Bibi took the wheel and decided to whisk us off to the Fruit Bowl–an impressive canyon famous for being a stage for the local highlining scene–a few miles out of town. Making sure to keep in the running theme of firsts, I was encouraged to go for a walk on my first ever highline. If I’d felt like I was in some sort of lucid dream due to a lack of sleep, I was readily plucked from it and placed in the middle of a void with one inch of webbing suspending me in a terrifying and magnificent amount of space. This made certain I was kept awake and that the first day’s whirlwind tour was pressed into my memory like a brand on a cow’s back.

Before I knew it, weeks had transpired and Yosemite felt no closer than it had been on day one. I’d look up the weather for The Valley and see some severe drops in temperature. Apparently, the area was experiencing an unusual bout of cold and wet weather for the season.

I’d scroll through social media and see all the people huddled in their sleeping bags on the ground, queuing up for days to claim a camping spot. I’d then find myself reluctantly comparing it to the perfect cracks, uncrowded crags warm in the sun, and all the open space I’d been experiencing at The Creek.

The mental scales would make themselves apparent and I’d inevitably weigh it all up against the logistics of big-walling El Cap, the paid sites and the bustle of tourists.

My dream of the big stone was still nagging, but I just wanted a few more days to enjoy what was in front of me. Somehow it felt like I was cheating on my own dream– having some sort of affair, but something about this brand of freedom was intoxicating and very much addictive. Maybe it was laziness or the idea of cold granite and wet weather, or maybe without realising it, the desert had already begun to wrap me around its little finger.

I’d put the weather forecast for The Valley away, close social media, and I’d find myself driving out to The Creek again the next morning.

During the drive out there I would often catch myself lost in thought about a project I was getting close to, the aesthetics of a particular splitter, or the ease of access to more climbing than I could chew. Eventually, my Dodge would take the turn off at Beef Basin, and I’d see the teeth like silhouettes of The Bridger Jacks and The South Six Shooter forming the definitive Indian Creek skyline. Their stark, statue-like features framed against the deepening bloody red of the afternoon sky, and gradually disappearing in my rearview mirror.

When I finally pulled up at camp I would make tea, sit on a log and absentmindedly stare through a clumping of cottonwood trees. The leaves were yellowing with the change of season and I remember seeing stars beginning to prick themselves into the sky. I would spend the last hour of light scanning the wingate sandstone walls, and make out countless world-class cracks in every direction.

My newfound friends and I had all but turned the cottonwood campground into our own community, and by luck, we had it to ourselves.

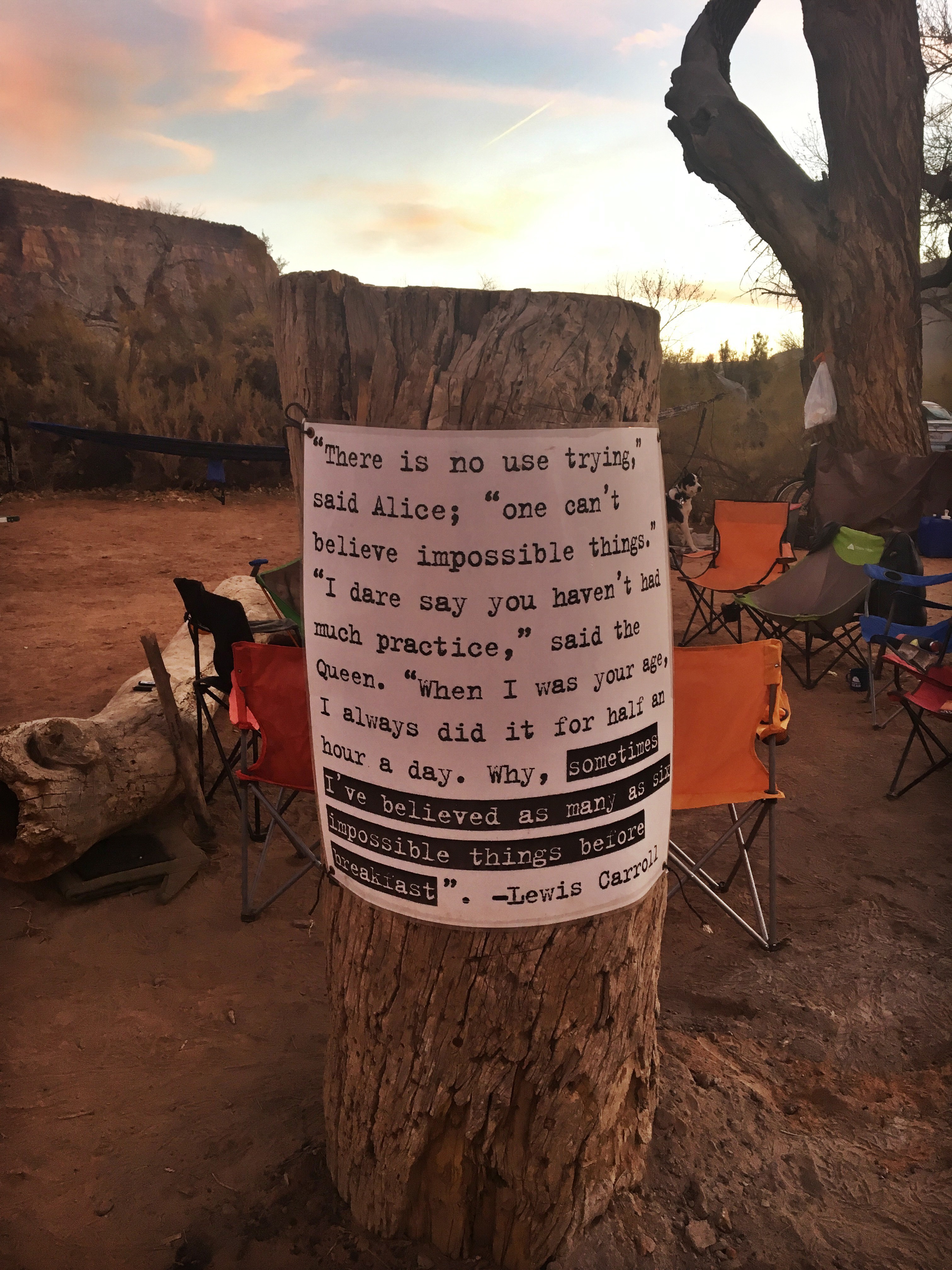

The cook-ups became a desert version of My Kitchen Rules. There were Alice in Wonderland quotes pinned to stumps. The making of a fire would–as if churchgoers summoned in ritual–coax everyone out of their vans. This would give way to a torrent of sharing the day’s hard-won ascents. Cheap beer loosened tongues and empty cans became laughter. Flutes, drums, and sometimes even electric guitars hooked up to car batteries would make raucous song. You could become hypnotised by a fire spinner lost in dance, or greeted by an entrepreneur called ‘Disco’ with a tip of his glitter top hat as he invited you to party on his bus.

Passion of all kinds was spread thick like cream cheese on a bagel.

Inconsequentially we had forged a ragtag group of desert dwellers, who despite mummified hands covering gobies and torn skin, could only think of one thing–climbing more cracks.

I make it sound romantic, and no doubt some parts were, but in reality, dirtbagging isn’t easy. Though the Fred Becky impersonators with 100,000 followers on ‘the gram’ have a clever way of making it look cool, eating soy sauce and rice for days on end, isn’t, in any classical definition that I know of, cool.

However, the freezing cold nights in the van, the constant hunger, the soreness felt from head to toe, the chapped lips, the sunburn and the dust-laden clothing, seemed only to emphasise every moment of content. It made the colours at sunset seem more vivid, the sense of community amongst us strong, every meal sweet, and the willingness to share, generous. It made our appetites to keep pushing ourselves on the rock day after day, insatiable.

And this is exactly what hooked me.

Maybe I’m another token Australian glorifying the West. Hoping I’d find Clint Eastwood standing in the middle of a dust plume on the road to the crag, an all but gone cigar held in a set jaw, eyes squinting in the sun with a thousand-yard stare. I probably am and I’ll own that, but at its core, the feeling of freedom in The Creek was inescapable.

I was often left wondering how many places on the climber's tick list can still boast of this sort of freedom anymore. The pioneering days now stories followers relish in retelling. The 60’s era Camp 4’s of the world are probably very few if not long gone. Indian Creek isn’t exactly somewhere out of the spotlight, but for somewhere as esteemed and loved, as world class in its climbing and as unique in its style, it still felt wild at every turn.

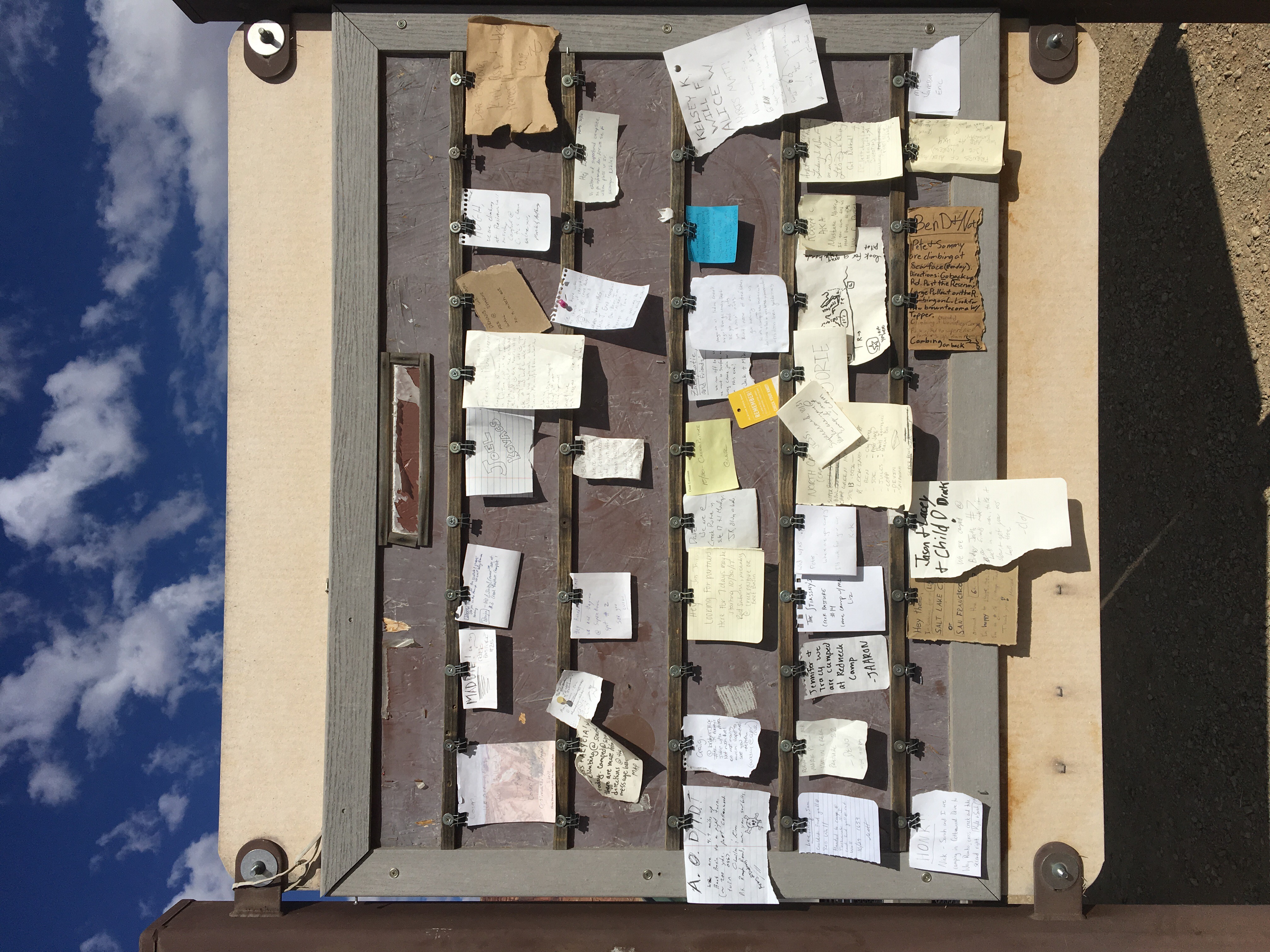

Its charm lay in the dirt roads, the lack of phone service, the community notice board that served as the only form of communication, the driving of cattle still done on horseback, and the petroglyphs that speak of a distant past. It was not the same Indian Creek that the Navajo or Anasazi people knew, or the same Indian Creek that Steve Hong is rumoured to have flown into during his early days, cherry-picking untouched soon-to-be classics with not a soul in sight. But it was a place that seemed to remain in its own version of time, slowly sewing its cryptobiotic crusts and hanging on to life.

It seemed that everyone I met out there had a deep respect for The Creek. They understood it was a place you needed to be mindful in caring for. So it could continue to inspire those of us inclined, to stuff our hands, feet, and limbs into the fractures of geologic entropy, and ultimately feel part of something special. I felt privileged to be there, as I try to be when climbing anywhere. However, this was a special sort of privilege. An admiration for its fragility was always present.

Time out there wound up feeling stretched. It became a stream of days that flowed seamlessly into each other and the only way in which they ended up being divisible, was by the peculiar or extra special moments between them.

One such moment occurred when I was invited to my friend Bibi’s camp at Creek Pasture to have some beers and organise the next days climbing. As I approached I remember hearing the sound of a banjo and another instrument I wasn’t familiar with. Being a musician in a life before climbing this excited me. But that excitement quickly turned into bewilderment as I rounded the parked vans and the firelight illuminated the face of the banjo player. It was one of my all time climbing heroes, Mason Earle.

The guy jamming with him was Said Belhaj, another climbing luminary, and sport climbing legend. I’m still not sure how this all happened but after gaining some composure I introduced myself and sat on a cooler to jam along with what they were playing. I inquired to Said about the instrument he was playing and he informed me it was a Moroccan Guimbri, it looked like an elongated cigar box with three strings. The clear twanging of the banjo and the earthy thrum of the guimbri created an exotic mash that was strangely fitting to the desert landscape around us.

For a long while I couldn’t believe the situation I was in, but as we became lost in each new rendition of the music, I also lost the daunting feeling of being in the company of two very talented pro climbers, and as it turns out, astute musicians.

We all shared some mulled wine, talked about where we should go climbing the next day and I was reminded that they were just people, who, like us, had a fondness for The Creek.

The next day while we were at the crag, a friend of Mason’s nicknamed ‘Q’–aka James Q Martin–came along to take some shots of Mason retro-onsighting a 5.12 and going on 5.13+ called “Less than Zero”.

A friend and I got talking to Q and he told us of a film he was making called “The Cowboy and The Climber.” Q explained it was about a climber (himself) building a relationship with the local Indian Creek rancher and a trading of their respective crafts. Q would learn how to work the ranch, and the rancher would learn how to climb from Q. From what I understood, he wanted to create an understanding and an appreciation of the ways in which the land here is used.

Q is a well-known conservationist and has done some incredible work with the community to keep areas like Indian Creek places we can come and enjoy as climbers. Talking with Q that day made me realize that a hard political battle was fought to keep this place open and accessible for recreational use. That educating people to have a respect and responsibility of care for the land was integral to keeping places like this open for future generations.

As an Australian it made me appreciate the environments back home that are fragile in the same way as Indian Creek. After meeting Q that day I was left with the feeling that we should be treating them with the same level of respect.

One night I met a man at camp called Ivan, who had an admirably youthful energy and who after striking up a conversation, invited me to climb with him the following day. He was completely unassuming, sitting in the back of his pickup-truck-turned-#vanlyf, reading a book and scratching his dog Rudy behind the ears. He was out here because, as he put it, “I love cracks, and it’s the best crack climbing anywhere.”

As we climbed throughout the next day, I’d gleaned enough from our conversations to learn he wasn’t just some older guy with a love of climbing. I discovered that I was actually in the company of a true Creek aficionado. He had been climbing here before I could tie my shoelaces and had put up some first ascents with David Bloom, the author of the Indian Creek guidebook. That day he granted me the insiders story to The Creeks years of inception, the venerable golden years, the successful ascents that marked them and the failed ones that hadn’t.

He taught me how to rand smear on tight finger splitters, how 20-year-old cams may look horrifying but can still classify as bomber. He also demonstrated that cracks that appear unremarkable and obscure, generally meant that in order to climb them you needed to do some remarkably obscure things. I think he was trying to show me that they shouldn’t necessarily be overlooked. I understood the sentiment, but when he lowered down and offered me the sharp end I declined the offer as graciously as I could.

Something about that day in particular solidified the whole experience. Amongst the parties in buses, Creeksgiving and Halloween celebrations, jamming with some of my climbing heroes, and enjoying more climbing in a short period than I ever have in my life, that day stood out.

I wasn’t sure why I felt this way for a long time but now I look back and I believe it was seeing the love of a place through another person’s eyes and this somehow confirming how I felt.

He’d been here uncountable times, and it still seemed as if he was excited as ever.

From one moment to the next, the magnet that had been El Cap slowly began switching poles until my iron filling was eventually immovable, buried in red dust.

Sometimes spontaneity can take us like a strong current, changing the course of our plans so much that we wonder how we got there. Sometimes our original dreams get lost somewhere along the way but in the process, you realize the ones you weren’t aware you had.

My dream wasn’t necessarily to say I climbed El Cap or to stand in a stupor in the meadow, ogling up at the valley giants, contemplating my insignificance. My dream was to learn new skills, throw myself into another world, roll with the punches and ultimately feel a sense of freedom. That at the drop of a hat I could be experiencing something entirely new. That dream came true in every sense.

One morning I drove into town, walked into the local Gear Trader store in Moab, and I sold my extra ropes. I used the money for food and water, fueled up the dodge and drove straight back to The Creek.